The notion of killing cats to safeguard native birds is not new among conservationists and was as deeply ingrained in the inter-war period as it is today. By Anton Sveding

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

When economist and philanthropist Gareth Morgan suggested a nationwide eradication of domestic cats in 2013, it caused a public outcry. Five years later, Southland Regional Council proposed a ban on all new domestic cats in the small village of Omaui to protect the area’s birdlife.

The council said hearing and seeing tūī “would more than make up for not being able to own a cat”. But a majority of the village’s human inhabitants disagreed. One argued cats played an integral role in combating the high number of rats and compared the proposed ban to the actions of “a police state”.

While proponents of cat bans or even nationwide eradication of the species have met with strong resistance, even being portrayed as cat-hating fanatics, neither Morgan nor Southland Regional Council were among the first to label cats as a menace to native birds.

On the contrary, the notion of killing cats to safeguard native birds is deeply rooted in the New Zealand conservation movement that emerged in the early decades of the 20th century.

Propaganda efforts by leading bird preservationists in the interwar period tried to convince the public of the menace that cats pose to native birds and that cats ought to be destroyed in the name of bird preservation.

This can particularly be seen within the Native Bird Protection Society, founded by Val Sanderson in 1923 and today commonly known as Forest & Bird.

This article does not take a position on whether cats should be killed to protect indigenous avifauna. Rather, it seeks to highlight the necessity of a historical perspective when discussing the complex relationships between humans, cats, and native birds in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Cats were among the first animals introduced by Europeans to Aotearoa. On his first journey (1768–1771), Cook reportedly gifted two cats to local Māori at Uawa on the eastern coast of the North Island. Cats’ appetite for native birds was recorded on Cook’s second voyage, when naturalist George Forster observed the ship’s cat regularly jumping ashore for a meal.

Yet, despite being one of the first European animals to set paw onto Aotearoa soil, cats have been largely overlooked in its environmental historiography. In fact, cats have received limited attention among scholars of biological invasions in general.

Following the arrival of James Cook’s Endeavour, the cat population steadily increased with the growing number of sealers and whalers, and settlers from the 1840s. Soon cats had spread throughout the colony, causing havoc among native birds and contributing to the demise of some species and various degrees of endangerment of others.

During the interwar period, the Native Birds Protection Society (later Forest & Bird) embarked on a campaign to safeguard New Zealand’s indigenous avifauna. This included educating the public on the dangers that cats pose to native birds.

It employed both scientific means, such as statistics, and emotive evidence, such as pictures, cartoons, and photographs, showcasing the menace cats posed to native birds through its magazine.

In 1925, Sanderson featured a children’s story in the journal about siblings Billie and Mary, who encountered a cat staking out a nest containing four grey warbler chicks. Their father set up a trap and the following morning found “a very angry cat” inside it.

The story ends ominously: “Father smiled to himself and getting a sugar bag from the kitchen managed to finally get puss inside it. ‘I thing [sic] those little birds are worth a dozen of your kind,’ he said to himself, and no one ever saw that black and white cat again.”

Birds, issue 23 (1931). Image supplied

Usually, the cover of the magazine featured pictures of native birds, but in March 1931 it showed a stalking cat on a branch about to pounce on a bird’s nest. Possums, mustelids, and other animals may cause greater damage to birds in rural areas, but the Society was portraying cats as the primary threat to birds in urban areas.

To leading bird preservationists, such as Sanderson and naturalist William Herbert Guthrie-Smith, cats constituted a major danger to native birds, a view they expressed in newspaper articles and books.

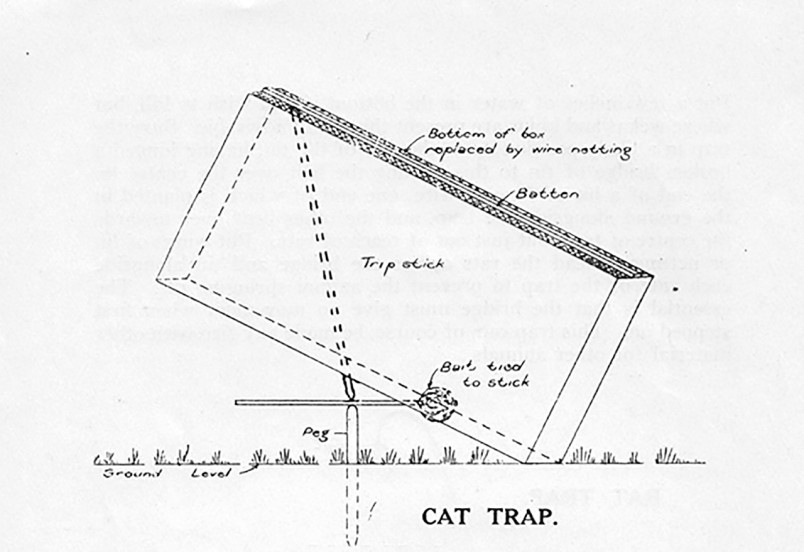

Sanderson also offered practical tips for protecting birds in the garden, publishing a number of trap designs, including this one for cats in 1932.

In 1933, Leo Fanning, a journalist hired by the Society to write articles for newspapers, described cats as “destroyers of native birds” and called for “something suitable for the control of predatory cats”.

Birds, 27 (1932). Image supplied

The following year, Sanderson called for cat control legislation in an article in Forest & Bird’s magazine arguing that licensing cat ownership was important and berating the lack of action by authorities in response to the “grievous nuisance of cats”.

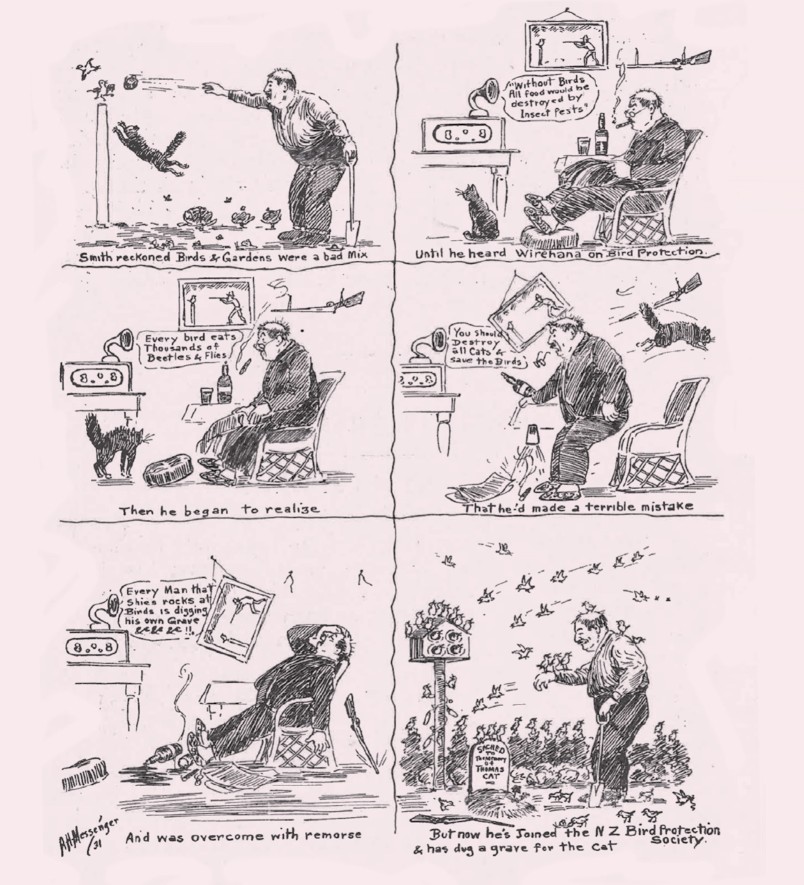

When radio ownership increased dramatically in the 1930s, Sanderson quickly employed the new medium to further the Society’s aims. An enthusiastic member known only as “Wirehana” started making radio broadcasts about the benefits of birds in New Zealand.

In 1934, to support Sanderson’s call for stronger cat controls, “The Convert’s Reward” sketch by Vice-President Arthur Messenger appeared in the Society’s magazine. It illustrated the process of a bird antagonist transforming into a bird conservationist as a result of the radio broadcasts.

“The Convert’s Reward”. Illustration Arthur Messenger, Forest and Bird, issue 33 (1934).

The sketch asserts that cat ownership was incompatible with bird preservation. Indeed, for birds to regularly visit one’s garden plot, both cat and hunting rifle had to be put down, as we can see in the final frame.

Forest & Bird’s cat advocacy continued into the 1940s. “Compulsory registration of cats was suggested at the annual meeting of the Forest and Bird Protection Society last night, as a means of protecting birds,” declared the Evening Post in April 1942.

“It was even suggested that nobody should be allowed to keep a cat.”

Newspapers of the day became sites of fierce debates regarding whether cats constituted a threat to native birds, with cat advocates emphasising the importance of cats as companions to humans and as hunters of rats, arguments that continue to be used today.

Indeed, when compared to present day debates, arguments largely remain the same, with proponents of cat bans highlighting the joy of hearing and seeing native birds, as well as expressing concern for native birds’ preservation.

This demonstrates the long, complicated, and to some extent emotional history of species valuation. Moreover, it illustrates the necessity of a historical perspective when discussing human–animal relationships in Aotearoa, in particular when it comes to birds and cats, animals that so many hold dear.

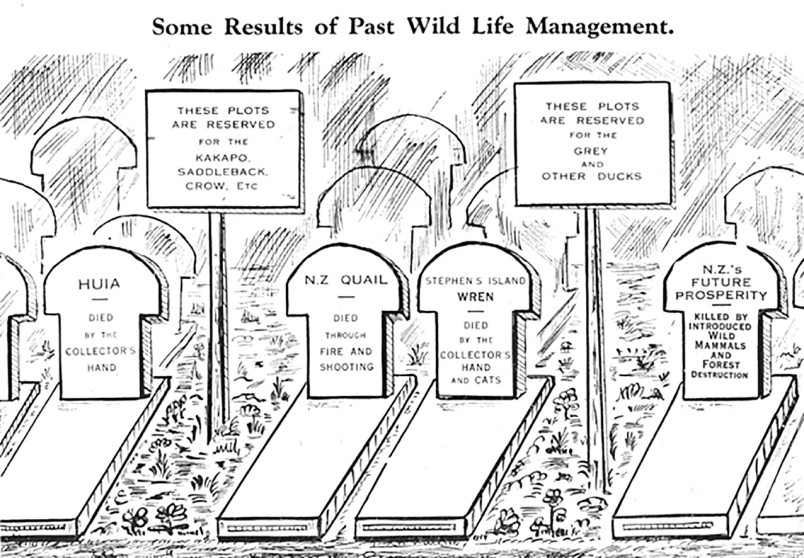

Cats were partially blamed for the demise of Lyall’s wren. Forest & Bird cartoon, 1937.

Anton Sveding is a post-doctoral research fellow at University of Agder, Norway. This is an edited version of his article “Cats and Native Bird Preservation in Interwar New Zealand”, which was published in the New Zealand Journal of History, 56, 1 (2022). Anton carried out primary research for this article while a PhD student in history at Victoria University of Wellington. You can read Anton’s full article at https://bit.ly/46lpQo0.

ACT FOR CATS

Forest & Bird is working to get the Cat Management Act over the line this year in a win-win for wildlife and cat welfare.

Cats are the most popular pet in Aotearoa New Zealand, but thousands are dumped in the bush every year and left to fend for themselves.

Forest & Bird, and others, are calling for a national Cat Management Act that would introduce mandated microchipping and desexing for all pet cats.

This would reduce the number of strays and allow domestic cats caught in live traps to be reunited with their owners.

Thanks to your generous donations last year, Forest & Bird’s predator-free campaign team wrote a detailed expert submission in support of a Cat Management Act.

We’ve also given evidence to Parliament’s Environment Committee and advocated for a national Cat Management Act in communities and the media.

Now we need to show the newly elected government that tens of thousands of New Zealanders support a strong and workable Cat Management Act.

Doing nothing will lead to more local bird extinctions, biodiversity loss, animal cruelty, and disease.

You can make a difference for native wildlife by donating to support our cat act advocacy in 2024.

We are tantalisingly close to securing a landmark win for nature, but we need your help.

Please make a donation at www.forestandbird.org.nz/support-us/appeals/support-predator-free.

Act for Cats brochure image.

10 REASONS TO SUPPORT

- FIRST IN THE WORLD. A national Cat Management Act would introduce mandated microchipping and desexing for all pet cats. No other country regulates cats nationally.

- IMPROVE CAT WELFARE. Regulating cats means fewer will be abandoned to live as starving strays. It’s more humane.

- SAVE LOCAL WILDLIFE. Native birds, lizards, and insect populations bounce back once feral and stray cats are removed. Trapped microchipped pets can be returned to their owners.

- RESPONSIBLE CAT OWNERSHIP. A Cat Management Act would make owners more responsible (as dog owners are, thanks to theDog Control Act 1996). It’s only fair.

- CATS CARRY DISEASE. They carry the parasite causing Toxoplasmosis disease that can lead to miscarriage and birth defects in humans and sheep, and death in Māui and Hector’s dolphins.

- THE SPCA WANTS BETTER CAT MANAGEMENT. Including microchipping, desexing, and registering cats on a national database.

- COUNCILS SUPPORT A CAT MANAGEMENT ACT TOO. Local authorities are unable to manage cats effectively under existing legislation.

- CATS ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR 63 EXTINCTIONS WORLDWIDE. In Aotearoa, feral cats killed the last of our tiny endemic Lyall’s wrens in 1895.

- NO UNWANTED KITTENS. Desexing would mean fewer litters ... and fewer cats would end up stray and eventually feral.

- IT’S TIME TO ACT. Forest & Bird has been asking for a Cat Management Act since 1934. This year is the closest we have ever been to achieving this.