A booming post-war economy brought many challenges for the men, women, and children attempting to stop the country’s fast-vanishing nature disappearing forever. In part 2 of our history of Forest & Bird (1946–1979) – read part 1 here – we look at the Society’s growth into the regions and its first flax-roots restoration projects. We chart the path to the National Parks Act 1952, the first rat-free island in the world, and the fight to save Manapouri – regarded as a watershed moment in Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental history. By Caroline Wood

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Winter 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

The Society’s rising profile after the Great Depression and World War II saw a rapid growth into the regions with 13 official “representatives” located from Upper Northland to Southland.

However, branches were not encouraged under Sanderson’s leadership, with just four being established in the Society’s first two decades. Following his death in 1945, members started pushing for change – they wanted to form themselves into semi-autonomous groups that could work to preserve nature in their own backyards. But “branches” still weren’t permitted under the incorporated society’s constitution, so a workaround was proposed and “sections” allowed instead.

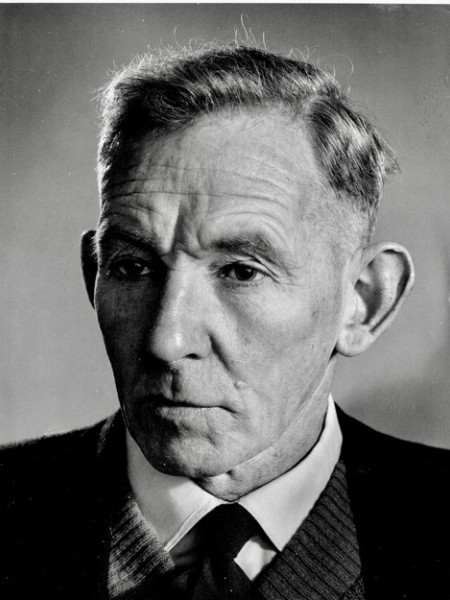

Lance McCaskill. Image supplied

The first was founded by Lance McCaskill in Christchurch in 1946, with Auckland and Gisborne following in 1947. Run by volunteers, the first sections advocated for nature locally and organised various conservation activities in their local communities, including guided trips to local scenic reserves and educational talks by conservation experts.

From around this time, they would also establish the Society’s first group-based conservation work, including local planting, weeding, and pest control projects.

In 1956, the Society’s constitution was changed so sections could become official branches, and community-based conservation began to take flight in Aotearoa, with Forest & Bird’s volunteers leading the way.

Thirteen sections and branches were established in the 1950s, followed by another nine in the 1960s, and 18 more during the 1970s. As the network grew to all four corners of the country, members played a vital role as the eyes and ears of the Society, feeding local intelligence to the Wellington national office on risks to nature from various threats, often the loss of native habitat through huge post-war economic developments – new roads, hydro-electric dams, farms, and housing.

A key focus for the Society since its inception in 1923 had been engaging children in a love of nature. In 1949, the first school groups were established, and many families experienced positive and sometimes life-changing experiences at a series of annual nature “family camps” held in national or local parks and scenic areas.

The first was in Waikaremoana, Te Urewera, in January 1953 and was described as “an unqualified success”, with 58 attending, including 14 children. The last was held at Lake Rotoiti in 1983.

Bernard Teague. Image supplied

The driving force and organiser of the family camps initiative was Society stalwart and keen deerstalker, hunter, climber, and tramper Bernard Teague (1903–82), who attended the inaugural event and gave one of the nightly illustrated talks called “In praise of Tuhoe country”.

Teague had explored the forests of Te Urewera in his 30s and was one of few pākehā to be familiar with the area.

Over the next six years, Teague’s family camps alternated between Waikaremoana and Taranaki, and around the country into the 1960s.

In 1959, there were two, one at Dawson Falls, Taranaki National Park, and the other at Rewarewa Marae, Ruatoki, Te Urewera. At the time, Teague was pressing for preservation of the forest in the Ruakituri catchment of the Wairoa River. In 1961, he was founding chair of Forest & Bird’s Wairoa section and won the Loder Cup in 1964.

He was a member of the Urewera National Park Board, served on Forest & Bird’s council for many years, and was elected Vice-President in 1969. He died in 1982, aged 78, having left a huge legacy for nature.

Ruatoki camp leaders, 1959: Bernard Teague (bottom right), Violet Rucroft (top left), Bessie Jarram (blue cardigan), and Alfred Morris-Jones (holding taiaha). Image Forest & Bird Archives

Into the world

In 1949, Forest & Bird became a member of International Union for the Protection of Nature, with the Society’s minutes showing a £12 bank draft was sent as the first annual subscription. Today, 70 years later, this organisation is known as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Forest & Bird is still a member. Based in Switzerland, there are 1400 members from more than 170 countries. The Society serves as one of seven official New Zealand members representing the interests of Oceania’s natural taonga on the international stage.

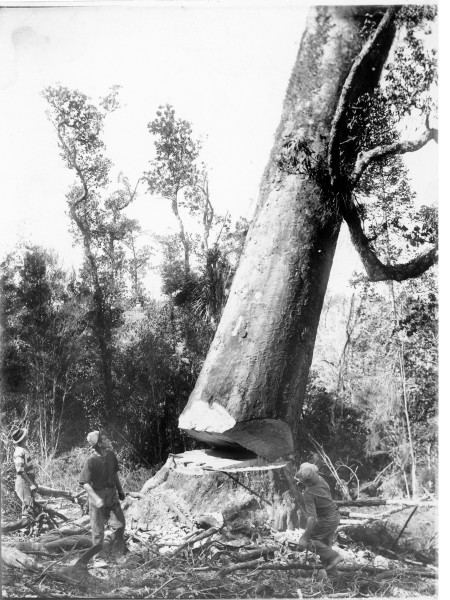

Kauri tree being felled by loggers, 1950. Image supplied

Waipoua giants

After World War II, the Society backed the efforts of Professor “Barney” McGregor, of Auckland University, to prevent the continuation of kauri logging in Waipoua Forest, Northland, that had been instigated as a war measure.

Forest & Bird joined three local preservation groups for a battle that continued fiercely until 22,500 acres were declared Aotearoa New Zealand’s first kauri forest sanctuary. It was officially opened in 1953, and Forest & Bird was invited to nominate a representative to sit on the Forest Sanctuary Advisory Committee. William Fraser, of Whangārei, became the Society’s first representative. McGregor was chairman of the Society’s Auckland Branch from 1950 to 1953 and 1965 to 1968. At the request of the Society, he prepared a large independent report on the effects of deer populations on New Zealand’s forests and steep mountain slopes that was presented to Parliament around 1964. McGregor, who died in 1977, will forever be remembered for having done much to preserve Waipoua, the only forest reserve set aside in perpetuity by a special Act of Parliament.

The 43ha Walter Scott Reserve was gifted to Forest & Bird in 1963 by sisters Mary and Lilian Valder. It is located in the Waikato. This photo shows a fencing party there in 1964. Image Forest & Bird Archives

Leaving a legacy

From the 1950s, we see an uptick in the number of New Zealanders gifting land with high natural values to Forest & Bird. In 1951, Hugh Alexander donated land that today forms the Society’s oldest reserve, Ngaheretuku, near Clevedon, south of Auckland. It contains significant stands of regenerating kauri and kahikatea forest and abundant birdlife, and Forest & Bird volunteers have been looking after it for the past 70 years. By the Society’s 50th birthday, in 1973, branch volunteers were looking after more than 2000 acres (809ha) of nature reserves all over the country.

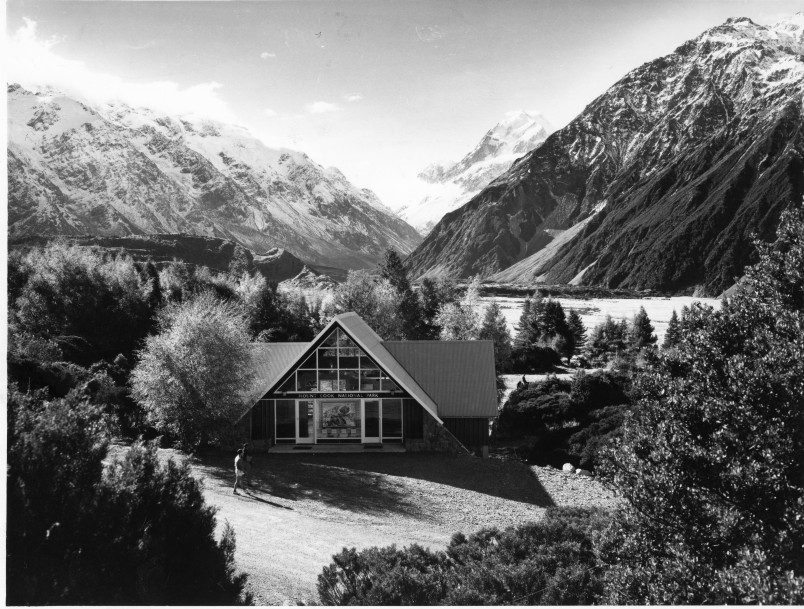

Mount Cook National Park headquarters, 1960s. Image Forest & Bird Archives

New national parks

One of the most significant pieces of environmental legislation ever placed on the statute books in Aotearoa New Zealand was the National Parks Act of 1952. It had the purpose of protecting in perpetuity, as national parks, for the benefit and enjoyment of people, scenery of such distinctive quality, or natural features so unique or beautiful, that their preservation is in the national interest. At the time, there were five national parks (Tongariro, Egmont, Arthur’s Pass, Abel Tasman, and Fiordland), and the Federated Mountains Clubs, Forest & Bird, and others had long lobbied for more to be established. A breakthrough came when the first National-led government came to power in 1949. FMC and Forest & Bird worked with the new Minister of Lands Ernest Corbett to create a series of the long-awaited new parks and reserves. Corbett, a dairy farmer from Taranaki, was the first Forest & Bird member to become Minister of Lands, as well as Minister for Forests and Māori Affairs. The conservative politician made excellent use of his position, adding 1.2 million acres (500,000ha) to the national parksystem and 147 scenic reserves. Between 1953 and 1956, he succeeded in bringing three new National Parks into the fold, all historically reserves – Mt Cook, Urewera, and Nelson Lakes. These were later followed by Westland and Mt Aspiring National Parks.

Predator-free milestone

In the 1950s and 60s, “noxious animals” – introduced mammalian predators and pests – were still a huge concern, with rats decimating birds on island nature sanctuaries, the march of introduced “opposums” northwards, and an ongoing deer menace all over the country. In 1960, a Forest & Bird junior section from Blackpool School, Waiheke Island, made history by systematically poisoning all the Norway rats that had recently swum to tiny Maria Island, in the Noises, and decimated a colony of ground-nesting whitefaced petrels. They and their indomitable teacher Alistair McDonald, with the blessing of the Wildlife Service (the forerunner to DOC), laid rat bait over the island and killed all the rats. The Wildlife Service took over the project in 1961 when McDonald left the island, and it was officially declared rat-free in 1964, in what we believe to be a world first. Over the next three decades, other Forest & Bird branches in Auckland and greater Wellington would help pioneer a series of landmark communityled island restorations at Tiritiri Matangi, Matiu Somes, and Mana islands.

Junior members of Forest & Bird with their teacher Alistair McDonald, Waiheke Island, late 1950s. Image supplied.

Alistair McDonald in 2019. Image Kevin Hackwell

Royal Charter

Queen Elizabeth II with Ernest Corbett, Minister of Māori Affairs, 1953–54. Image suppled

The Society received a Royal Charter from the Queen on its 40th birthday and became the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society in 1963. It had grown from a handful of members in March 1923 to 10,000 by March 1963. Around the same time, the Executive commissioned a well-known director, John O’Shea of Pacific Films, to make a documentary about New Zealand’s natural heritage and the work of the Society in protecting it. The Need for Nature was released in 1969 and shown before the main feature in cinemas all over the country during 1970. Today, the restored 16-minute colour film provides a fascinating window into the conservation concerns of the Society as it headed towards its first half century, with footage of Arthur’s Pass, the Wairarapa, Kāpiti Coast, Ruapehu, Tarapuruhi Bushy Park, and Waipoua, and shots of Forest & Bird members carrying out conservation activities.

Safety in islands

Roy Nelson. Image supplied

Maud Island frog. Image Zealandia

Securing suitable offshore islands to turn into bird and nature sanctuaries occupied the mind of incoming President Roy Nelson, who served from 1955 to 1974. He was desperately worried about fast-disappearing indigenous flora and fauna after huge swathes of habitat on the mainland were cleared to make way for post-war economic developments. In 1959, Nelson sought advice from ecologist Ian Atkinson, of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, on the availability of islands to buy for the purposes of conservation in the Hauraki Gulf and Bay of Plenty. Atkinson produced a list of possible candidates. In 1967, Nelson pledged a generous donation to help the government buy Mangere Island, Rēkohu, to save the Chatham Island black robin from imminent extinction. Then, in 1976, at the request of the Wildlife Service, the Society organised a fundraising appeal that smashed its targets and helped the government purchase Maud Island, in the Marlborough Sounds, to protect the endangered Maud Island frog. The rest of the money went towards the restoration of the karure kakaruia black robins’ forest habitat on Mangere Island, as described in our March 2023 issue.

Pivotal moment

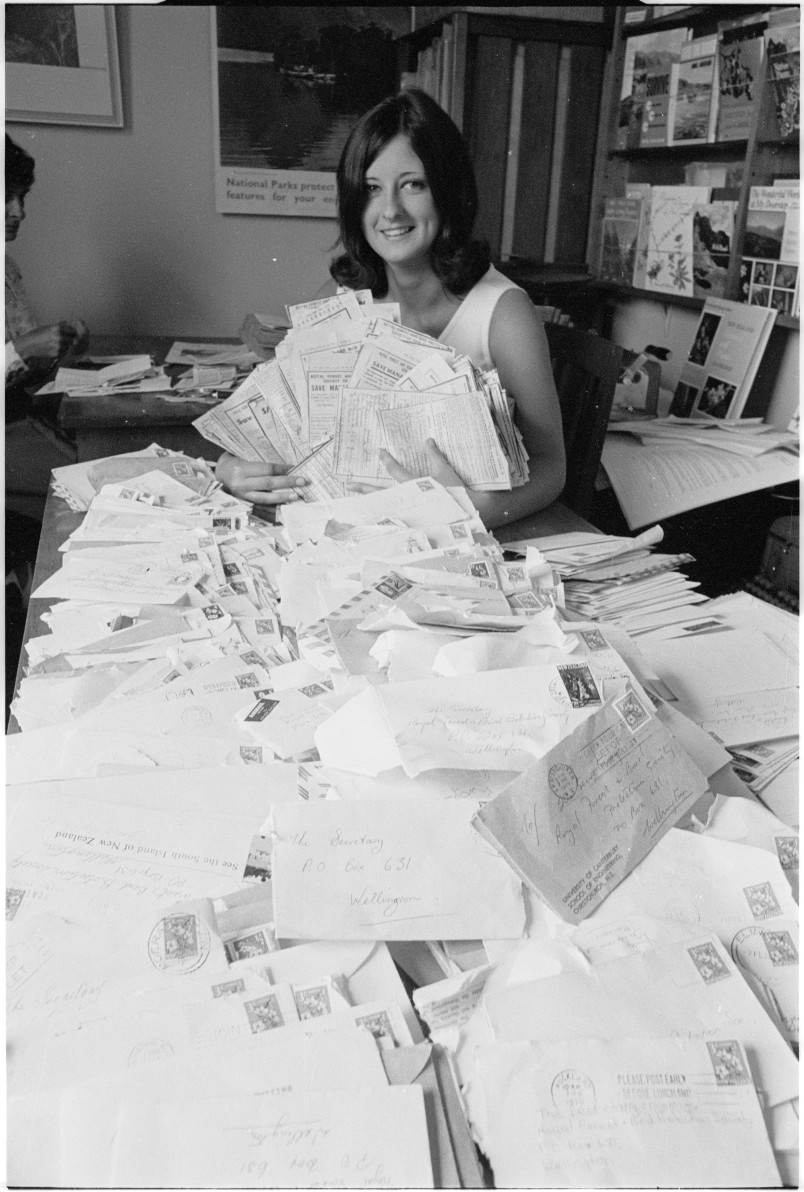

“Big hydro” electricity-generating schemes in the 1960s threatened some of New Zealand’s wild rivers and freshwater lakes and led to the Save Manapouri campaign, a turning point in New Zealand’s environmental history. Forest & Bird threw down the gauntlet in 1960 and spent the next 12 years fighting to save the lake in Fiordland National Park from being inundated as part of the Manapouri power project, including organising what was then (1970) the largest petition in the country’s history, signed by more than 260,000 people. The cost of the fight nearly bankrupted the Society, but the campaign was won when the incoming Labour government backed away from raising the lake in the face of mass protests. Plans to raise the lake’s water level were cancelled in February 1973. The huge outpouring of public anger radicalised a new generation of conservationists who joined the “cause” of nature protection, and environmental groups sprung up, including Greenpeace in 1974 and the Native Forests Action Council (NFAC) the following year. The dawn of the modern-day conservation movement had arrived, and Forest & Bird experienced a huge jump in membership, which hit 20,000 for the first time in 1975. The influx

of new supporters brought in more donations that allowed the Society to widen its reach and impact. The stage was set for some of the most tumultuous times in New Zealand’s environmental history.

Christine Foxall sorting Manapouri petition forms that were arriving at a rate of 4000 to 5000 a day in 1970. Image Alexander Turnbull Library

Further resources

- 100 Years and counting: A brief history of Forest & Bird’s work and impact is available for branches.

- The first 50 years of Forest & Bird magazine are freely available on the Papers Past website

- A brief history of 37 Forest & Bird reserves

- Examples and history of Forest & Bird’s posters (1923–73) + KCC’s first poster

- History and links to Forest & Bird’s early conservation films (1920s–1969): On request.

- For the official founding date of your branch, please reach out to Michael Pringle at m.pringle@forestandbird.org.nz.

Forest & Bird would like to thank the Stout Trust for its generous support in funding the Force of Nature history project. We also acknowledge the National Library of New Zealand and Ngā Taonga for their help in bringing these stories and many others to light. If you have any questions about Forest & Bird’s history project, contact Caroline Wood, at c.wood@forestandbird.org.nz