Fearing the Chatham Island robin was in perilous danger, three generations of conservationists battled to save them. By Caroline Wood

Once widespread throughout the Chatham Island archipelago, by the late 1870s the endemic black robin was confined to two small islands - Mangere and Little Mangere.

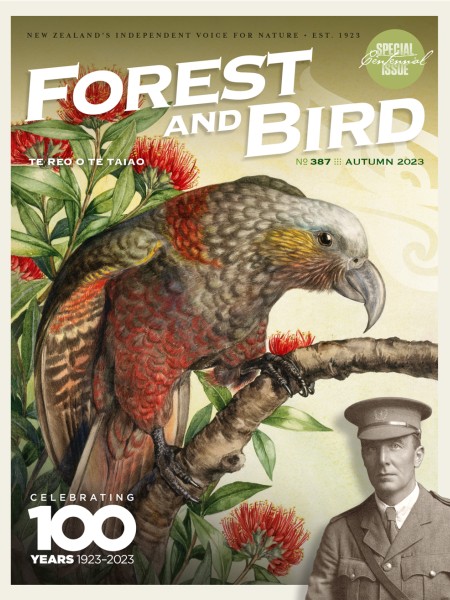

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

In 1938, a young Charles Fleming was one of the first to raise the alarm about the perilous state of the robins following a visit to Little Mangere Island accompanied by fellow Auckland University student Graham Turbott.

During a death-defying climb up the cliffs of the island, known as Tapuaenuku in Moriori, Fleming and his colleagues “rediscovered” a karure | kakaruia population but estimated there were only 20–35 pairs of black robins left.

They also documented other rare birds, including Forbes’ parakeet. But there was no sign of the Mangere rail, Chatham Island fernbird, or Chatham Island bellbird, all of whom had already joined the extinction list.

Charles Fleming at Tuku Farm, Chatham Island, 1938. Image courtesy Jean Flemming

Fleming, who was a great supporter of Forest & Bird’s work and went on to have an illustrious career as an ornithologist and conservationist, proposed protection status for Little Mangere. His series of scientific papers on the birds of the Chathams, published in 1939, remains a major contribution to knowledge of that area today.

In 1956, Forest & Bird published a four-page article in its journal Vanishing Species on the Chatham Islands, written by one of its members, who had visited the previous year.

Dr John Findlay alerted readers to the poor state of flora and fauna unique to the remote archipelago. Much of the damage was being caused by grazing farm stock.

He finished his article by saying “...most Chatham Islanders are nature lovers and would welcome any measure that would help save their wildlife heritage”.

Forest & Bird’s President Roy Nelson penned a strongly worded editorial next to Findlay’s article listing the plant and bird species that had already become extinct. He called for more botanical reserves to be established.

He also noted the New Zealand Wildlife Service had also raised concerns and recommended at least two areas be set aside “to preserve for all time some of the unique flora found there”.

Mangere Island with Little Mangere Island top right in 1969. The slope centre and left is where the main tree planting was done in the 1970s. Image Forest & Bird Archives

In 1961, Rangatira South East Island was gazetted a nature sanctuary and became sheep free. Once the browsing mammals had been removed, the indigenous habitat bounced back, showing it was possible to restore the bird’s habitat once pests were removed.

Meanwhile, on Mangere Island, “bush birds and petrels” had almost disappeared, according to a Lands and Survey Department report, most likely victims of the cats that had been liberated to control rabbits.

Roy Nelson wrote to Lands and Survey in 1963 setting out the many grounds that existed for making Mangere Island a wildlife sanctuary that could potentially receive transfers of endangered birds, including black robins, from Little Mangere.

He offered to help fund the island’s purchase, and, after some negotiation, Forest & Bird donated £2,000 (the equivalent of nearly $100,000 in today’s money).

This is how the akeake trees funded by Forest & Bird look today. Image Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

In 1963, the Crown bought Mangere Island for £3,454, including a generous contribution from the Society’s supporters, and it became a protected flora and fauna reserve, although cats remained a problem.

Next, Nelson offered to help the government buy more land on neighbouring islands, but the money was not needed. The government bought a 240ha plot known as the Glory Block in the centre of Rangiauria Pitt Island that contained relatively unmodified rat-free forest.

Nelson also attempted to buy Tapuaenuku Little Mangere Island so it could become a protected bird sanctuary, but he failed and it remained in private hands.

By 1969, there were only 15–20 pairs of black robins remaining on Little Mangere. Then, in the early 1970s, it was reported that cats had killed off 12 species of birds on Mangere.

The last two populations of Chatham Island black robins on Earth were in serious trouble.

Brian Bell in 2012. Image supplied

Brian Bell, a leading ornithologist and threatened species conservationist who was working for the Wildlife Service, approached Forest & Bird with a plan to save them.

In 1975, the society’s president John Jerram agreed to mount a fundraising appeal to help save the black robin. Jerram undertook to raise enough money in donations to plant 50,000 hardy Chatham Island akeake (Olearia traversi) over five years.

Once restored, the plan was to translocate the last seven remaining birds from Little Mangere to the larger more accessible Mangere Island.

Bell even suggested a slogan for the appeal “Save the black robin – adopt a tree at 50 cents”.

The society’s branches swung into action, seeking donations from all over the country, and the appeal was a resounding success, raising more than double the target amount in 1976.

The $14,000 supported the purchase and planting of 120,000 plants on Mangere Island. In 1981, wildlife photographer Rod Morris visited and reported the plants had grown above head height, providing shelter, leaf litter, and insect habitat for the robins and other species.

But the fate of the black robin was still hanging by a thread. By 1980, there were just five birds left and only one breeding pair – Old Blue and Old Yellow.

Don Merton with a Chatham Island black robin. Image supplied

It was up to Bell and his team, which included Don Merton, to save the species. They knew it was a race against time, having recently witnessed the loss of three unique species.

In 1964, the pair had been part of a heroic but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to save the last South Island snipe, the greater short-tailed bat, and the New Zealand bush wren from a rat invasion on Big South Cape Island, near Rakiura.

The black robin is a slow breeder, so Merton decided to try a cross fostering programme using Chatham Island warblers and tomtits as foster parents. This allowed the robins to produce more than one clutch per season.

The success of this world-leading technique was spectacular – by the end of the 1984/85 breeding season, the number of robins had increased to 38.

Old Blue produced the entire first generation of robins born on Mangere Island, securing her a place in the annals of New Zealand conservation. Her offspring prospered. She was the mother of six chicks and grandmother to 11.

A plaque on Mangere Island commemorates Old Blue's legacy. Image Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

In 2010, Don Merton received an Old Blue award from Forest & Bird for his outstanding contribution to conservation. He led the black robin recovery programme for more than a decade and played a key role in saving tīeke South Island saddleback and kākāpō.

Today, there are about 300 adult black robins, and the akeake forest planted with the aid of Forest & Bird donations is flourishing.

Leaving a legacy

Old Blue. Image Don Merton

Thirty-five years ago, Forest & Bird launched its Old Blue awards named after the Chatham Island black robin “mother” who saved her species from extinction. Since then, 201 men and women have been awarded an Old Blue in recognition of their huge contribution to nature protection in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Force of Nature | Te Aumangea O Te AoTūroa

This article includes previously unpublished stories collected by Forest & Bird's Force of Nature history project with funding from the Stout Trust.