The misunderstood cockroach gets a bad rap in Aotearoa, but our 15 indigenous species perform a vital role in the bush. By Ann Graeme

Carrying the shoulder bag of rat baits, I pick my way along the forest trail that is called Line 7 West. Ahead is the yellow bait station, nailed to a tree. I crouch down to open and refill it, and out scuttle startled cockroaches.

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

They startle me too! There is something creepy about cockroaches. I remind myself that these are native cockroaches, they are quite harmless, and they belong in the forest.

Worldwide, there are more than 4500 species of cockroaches. Every continent barring Antarctica has its own indigenous species, and Aotearoa has 15.

Cockroaches belong to an ancient order of insects called Blattodea.

Fossils show that they and their sister family, the termites, having been on Earth for more than 300 million years.

Back then, in the geological period called the Carboniferous, their ancestors dominated the insect community. It was a warm, wet world where forests flourished, and the cockroaches would have eaten decaying leaves and wood as our native cockroaches do today.

This winged native bush cockroach is not a pest. Parellipsidion sp. Image Bruce McQuillan

Cockroaches may be successful in terms of numbers and distribution, but in terms of human popularity, they are not. If you type cockroach into Google, the instant response will be “how to exterminate them”.

This tells you a lot about our attitude to cockroaches. They rank even higher than flies and spiders as the most reviled of creatures.

But the cockroaches that live in our houses are not the native species of the forest. Just as rats have travelled with us around the world, so have some species of cockroaches.

Three introduced species are pests in New Zealand, and their names betray their origins – German cockroach, American cockroach, and Gisborne cockroach.

Really? “Introduced” from Gisborne?

Despite its name, this large cockroach came from Australia. It is credited with first arriving in Gisborne in the 1960s.

The introduced Gisborne cockroach Drymaplaneta semivitta is harmless and prefers to live outside. Image Bruce McQuillan

This is a slight on Gisborne because the cockroach was recorded earlier in Auckland and Tauranga. Probably it came into port on a log ship, as it likes to live under bark and feed on wood.

Now it has spread throughout the North Island and into the top of the South Island. It is quite harmless, it does not invade our food, and it prefers to live outside in the wood pile.

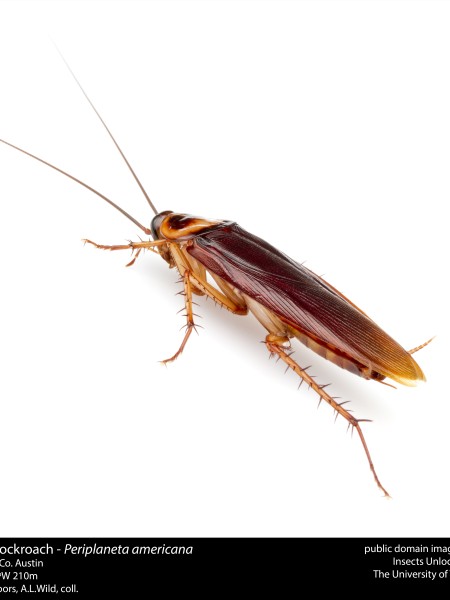

American cockroaches too are misnamed. They are native to Africa and the Middle East. They are thought to have arrived in America in the 17th century, quite possibly in the ships carrying African slaves to work in the plantations.

And the German cockroach is not native to Europe either but probably came from Southeast Asia. It is now the most populous cockroach on Earth.

People loathe all three species, but the Gisborne cockroach does not deserve such abhorrence. It is quite benign. It does not carry diseases, but it is big and seriously scary and has the alarming habit of appearing when you least expect it.

But the American and German cockroaches can carry diseases and transfer them to the food in your pantry. They, like house flies, have the unlovely habit of feeding and crawling over rotting matter, then transferring the contamination when they traipse over unspoilt food.

We combat cockroaches in our houses first by cleanliness, which denies them food, then by poisoning them. Cockroaches have a sweet tooth, so simple sugars are used as a lure for the poison baits.

German cockroach. Image istockphoto.com

But a strain of German cockroaches has evolved that finds glucose distastefully bitter. They won’t touch sweetened bait. This aversion has a genetic basis and is passed on to the cockroach’s offspring. This is a dramatic illustration of natural selection and adaptation. Cockroach baits may have to evolve too.

Back in the forest, native cockroaches feast on the cereal baits we put out for rats. Thankfully, we are not poisoning the cockroaches or the wētā and leaf-veined slugs that eat the bait too.

The toxin in the block baits is an anticoagulant that acts as a blood thinner in mammals. For us, a tiny amount, carefully prescribed, can be a life saver, reducing the danger of blood clots leading to heart attacks and strokes.

For rats, constantly chewing on the same toxin, it is fatal. Insects are quite unaffected, as their watery, greenish blood has quite a different composition to the blood of mammals.

So we can admire forest cockroaches, secure in the knowledge that they will never intrude on our houses but will keep on working, part of the vital recycling team that supports our native forests and their wildlife.

Adaptations for survival

The introduced American cockroach. Image Alex Wild

Modern cockroaches may have evolved into many species, but they still look very like the fossils of their ancestors. Their secrets of success lie in their form and behaviour:

- They have a characteristic flattened form that enables a forest cockroach to slip behind a flake of bark or a German cockroach to squeeze under the cupboard door.

- They are omnivores and scavengers, meaning they eat almost anything organic.

- They are fast. The American cockroach is considered one of the fastest running insects. In an experiment, it recorded a speed of 5.4km/h, which would be comparable to a human running at 330km/h.