Forest & Bird's Marlborough Branch volunteers have been trapping pest skinks in Blenheim. By Helen Braithwaite and Deleece Augustyn

Plague skinks were first found in the South Island in 2018 and immediately the word went out to lizard enthusiasts to check for this uninvited pest species, formerly known as rainbow skinks.

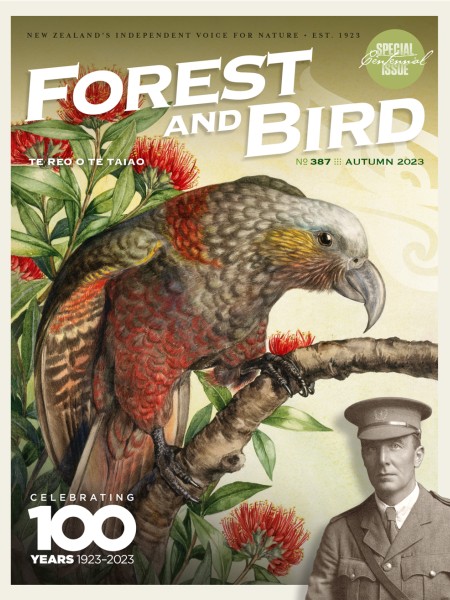

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

Luckily, only two established populations of the species were found. One was in Havelock and the other in the Riverlands-Cloudy Bay Industrial area on the outskirts of Blenheim.

The agencies decided to do some monitoring using traps to see how widespread the exotic species were. They also brought in a lizard detection dog to check the industrial area.

Forest & Bird’s Marlborough Branch was asked whether it would like to help prevent plague skinks spreading beyond the industrial area into a nearby native wetland.

It was feared the established population – living in long grass alongside an open drainage channel – was likely to spread to the Wairau Lagoons. This is a place of great significance to Rangitāne as well as a natural refuge for native lizards, plants, and invertebrates.

In 2019, under the supervision of the South Marlborough DOC office, Forest & Bird volunteers started trapping plague skinks alongside Co-op Drain.

The skinks are caught on sticky traps, which are pegged down and checked at least daily for three to five days.

The trapping occurs when the weather is optimal – not too wet, not too cold, and not too hot.

Too wet and the volunteers are at risk of slipping, too cold and the skinks are not out and about, too hot and the traps need to be checked more often.

Forest & Bird volunteers monitoring for plague skinks in Blenheim. Image Deleece Augustyn

The team has been trained to identify the pest species and carefully release native lizards, which unfortunately have been found only downstream of the industrial area.

This is an indication that natives are being displaced, as they were previously found in the original surveys.

Over the time we have been trapping, the team has put out 3022 traps and dispatched 711 plague skinks.

The work is not too tedious, taking a few hours – usually two hours to set up, plus one hour to check the traps each day, and two hours to clear up on the last day of a trapping cycle.

We have a pool of volunteers who come and help if they are available. Because of the easy terrain, the lightweight traps, and the easy distance to Blenheim, it is a bit different and less physically demanding than other trapping programmes.

Recently, we met up with a local lizard enthusiast Jozef Polec, who has been great at answering our questions, telling us interesting information about lizards, and showing us the finer points of trap placement and other lizard-monitoring methods.

Overall, we are pleased to have established a good connection with Marlborough District Council, in particular Steve Bezar from the drainage and floodway engineering department.

Moving forward, we would like to establish relationships with landowners and companies where we suspect plague skinks may be inhabiting, so we can access these sites and carry out surveys and monitoring.

In future, we hope to raise funding to carry out a three-year survey to confirm which skinks and geckos are present in the Wairau Lagoons area and check plague skinks have not made it that far.

Wairau Lagoons, Marlborough. Image Ricky Wilson/Flickr

Plague skinks are widespread throughout the North Island, but anyone finding these pests in the South Island is encouraged to contact Marlborough Forest & Bird at marlborough.branch@forestandbird.org.nz and also contact the Ministry for Primary Industries on 0800 80 99 66. If possible, please provide a clear picture and map location.

What are plague skinks?

The plague skink (Lampropholis delicata), which was previously known as a rainbow skink, originates from Australia. They have been in the North Island since the 1960s but had never been seen in the South Island until relatively recently.

Introduced plague skinks compete with our native skink species for resources such as habitat or food. Plague skinks differ in their breeding methods to most of our native lizards and reproduce faster. They lay eggs and produce larger clutches of young. By contrast, native species such as grass skinks are viviparous – they give birth to live young and often have lower numbers of offspring.

Being omnivorous, plague skinks also threaten native plants and animals. They eat crickets, snails, worms, beetles, flowers, small fruits, spiders, and even other small lizards.

For more information, go to www.doc.govt.nz/nature/pests-and-threats/animal-pests/plague-skinks.