2020 marks the 50th anniversary of Forest & Bird’s record-breaking petition that saw nearly one in 10 Kiwis signing to save Lake Manapōuri. By Caroline Wood

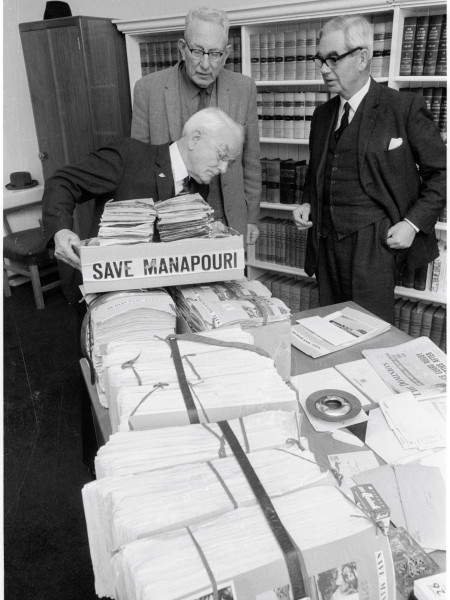

On 26 May 1970, officials wheeled piles of slightly tatty cardboard boxes into Parliament. Television footage of this moment shows bundles of SAVE MANAPŌURI petition forms stacked on a hand trolley being delivered to the Minister of Justice, Dan Riddiford, who was waiting to receive them along with Forest & Bird’s president Roy Nelson.

The 1970 Save Manapōuri petition is delivered to Minister of Justice Dan Riddiford (right) with Forest & Bird President Roy Nelson (centre). The Dominion Post Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library.

An Evening Post photographer was there at Parliament to capture the historic moment. At the time, it was the biggest petition New Zealand had ever seen. An incredible 264,907 people signed to save two remote Fiordland lakes, Manapōuri and Te Anau, that most of them had probably never visited. The petition was organised by Forest & Bird, and the first two people to put their names to it were Roy Nelson and fellow Society stalwart Lance McCaskill.

The massive petition was a turning point in a long-running battle between conservationists and the government. After ignoring two previous Forest & Bird petitions in 1960 and 1963, this time ministers couldn’t ignore the strength of public opinion expressed in page after page of scrawled hand-written signatures.

What was to follow over the next two years changed a nation and heralded the arrival of the modern day conservation movement, including the establishment of many environmental groups and the formation of an umbrella group, CoEnCo, later ECO.

“The petition, which so many Kiwis signed, was a nuclear moment of 1970,” says Lou Sanson, Director-General of the Department of Conservation. “It was the start of the modern-day ecological movement. The next big battle was for the forests.”

For Forest & Bird, it would kickstart a transformative period that would see its membership nearly double from 5700 in 1959 to 11,000 in 1971 and then rise massively again over the following decade to reach 36,000 in 1983.

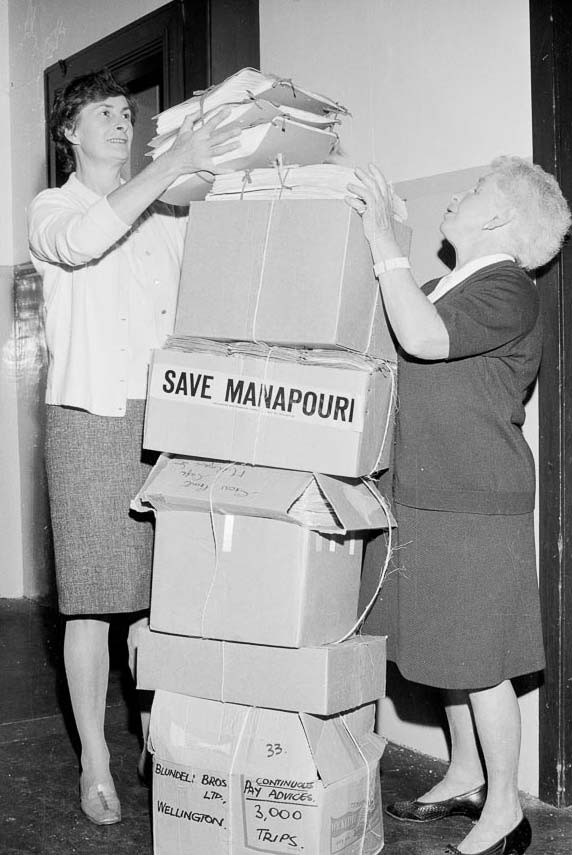

Forest & Bird staff members support a 1.5 metre tall pile of boxes containing the 'Save Manapouri' petition in 1970.

At the time, Forest & Bird was the only large national conservation organisation in the country. With its financial clout, network of passionate volunteers, and branches around the country and a national office in the political heartland of Wellington, the Society was well placed to support the many organisations and individuals who would emerge in the late 1960s and jointly campaign to save Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau.

Over 15 years, the Society spent upwards of $400,000 in today’s money on helping to save Manapōuri, with a significant proportion of the total going towards organising the record-breaking 1970 petition and paying for a legal expert to represent conservationists at the subsequent Commission of Inquiry. By 1971, its coffers had run dry after spending a record amount on Manapōuri, and it was forced to dip into its reserves to fund a huge budget deficit, the equivalent of $180,000.

AND SO IT BEGINS

Lake Monowai was raised in the 1920s for one of New Zealand’s first hydro-electric schemes, causing huge environmental damage. Forest & Bird archives

The Dunedin branch was the first to raise the alarm. In January 1957, it wrote to Forest & Bird’s national office about government proposals to dam and raise the level of iconic Lake Manapōuri, a place of unparalleled raw beauty in Fiordland National Park. The plans would allow for a huge hydro-electric power scheme that could power a new aluminium smelter to help the country out of an economic crisis. In response to the branch’s concerned plea for action, Forest & Bird’s national executive immediately wrote to the State Hydro-electric Department demanding it share the proposals for the area. The department replied, claiming there were “no present proposals for this development”.

But secretly the government was working on plans, and, in June 1959, the Society’s leadership learned the government had authorised Australian surveyors and geologists to enter Fiordland National Park to examine the use of Lake Manapōuri for a hydroelectric scheme. It authorised all its branches to call public protest meetings, says Norman Dalmer, an eyewitness to the Society’s Manapōuri campaign, in his book Birds, Forests and Natural Features of New Zealand.

In January 1960, the Evening Post announced the Nash Labour government had signed a deal with the Consolidated Zinc Company (Comalco) of Australia, granting it exclusive use of the water from Manapōuri and Te Anau lakes for power generation for 99 years. The agreement also allowed Comalco to raise Lake Manapōuri by 100ft, drowning ancient beaches and pristine native forest along the shoreline and raising fears a Lake Monawai mark II would result.

“Conservationists were incensed by the government’s deceit – even more so when they discovered that the scheme was to be built in a national park, in violation of the National Parks Act 1952,” says Catherine Knight, in her book Beyond Manapōuri.

Forest & Bird swung into action and, in March 1960, presented its first petition to Parliament, with nearly 25,000 signatures asking the government not to ratify the Comalco agreement, not to raise the lake level, and that the National Parks Act be amended to provide greater security for national parks against commercial exploitation.

An editorial in Forest & Bird’s magazine said the Comalco agreement was “illegal” and shrouded in secrecy at the time of signing and that the Society “took steps to start an action at law to restrain both parties from operating the agreement ... but were reassured that no actual construction work would be carried out so didn’t need to”. It was a “bitter disappointment” when it realised that the reported agreement between the government and company was not all it seemed.

In September 1963, infuriated by the government’s ongoing secrecy about its plans for Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau, Forest & Bird launched a second petition, together with the Scenic Preservation Society, which 1127 people signed, calling on the Ministry of Works to make public “without delay, all the facts and figures relevant to the scheme” and show why it doesn’t prefer an alternative scheme that preserves the current water levels and doesn’t “destroy trees around the shorelines”.

TURNING POINT – FOREST & BIRD’S THIRD MANAPŌURI PETITION

Through the rest of the 1960s, Forest & Bird kept plugging away, using science and the law as cornerstones of its Manapōuri campaign. They believed raising the lakes would be an ecological “disaster”. But it wasn’t enough to shift the government from its preferred path. Something more was needed and that turned out to be “people power”.

Forest & Bird published five cover stories about Manapōuri during its 13-year campaign to save it. Forest & Bird archives

In May 1969, the Forest & Bird journal carried a cover story – “Lake Manapōuri Scenic Gem” – that warned construction work on the power station was well advanced and there was little time left to prevent a tragedy. At this point, no move had been made to raise the lake levels. “We have always considered that the raising of lake levels would be an act of almost incredible desecration and we have not yet been given any reason to change our opinion,” wrote President Roy Nelson.

A pivotal moment came in October 1969, when the Save Manapōuri Committee was set up after 10 concerned members of the community met in local politician Norman Jones’s home in Invercargill. The campaign was led by Southland sheep farmer Ron McLean, who set off on a national tour in early 1970 to raise awareness of the plans for the lakes, and within months 14 local campaign committees had sprung up throughout the country. Three years of huge public efforts to save the lakes followed, involving many organisations and individuals.

At a Forest & Bird council meeting at Bushy Park, in November 1969, the Society’s councillors asked for a telegram of protest to be sent to the Prime Minister in the hope of obtaining an assurance that the lake levels would not be raised. This was not forthcoming, and a “Dominionwide petition to protest was raised”, writes Dalmer.

Copies of Forest & Bird’s third Manapōuri petition were distributed to all members inside the February 1970 issue of Forest & Bird. The journal’s cover story “Is Manapōuri to be ravaged for dollars and cents?” was accompanied by an editorial that said: “People who stand firm when national natural treasures are threatened by clamour or greed for a few more dollars ... are people of character whose children and their children will have no cause to be ashamed of their forebears in years to come.”

The Society decided to advertise “on the breakfast session of all New Zealand radio stations” and sent a telegram to all branches and sections requesting they place petitions and leaflets with shopkeepers in all towns in their areas.

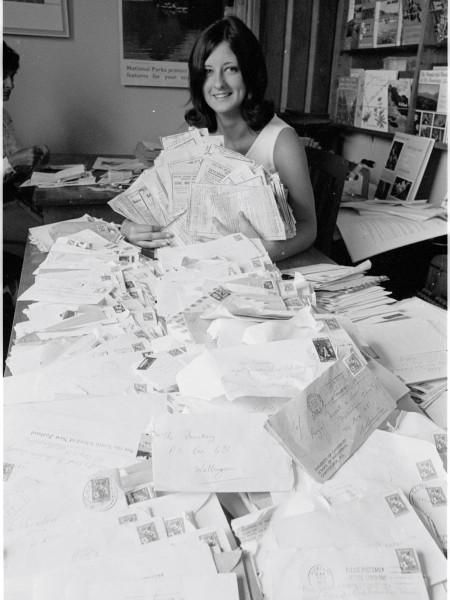

Christine Foxall, of the Royal Forest and Bird Society, holds forms signed by people opposed to the proposal, which were arriving at a rate of 4000 to 5000 a day. The Dominion Post Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library.

The response was staggering – at one point, staff were receiving 4000–5000 petition forms a day into Forest & Bird’s Wellington office. The Society was forced to take on three extra people to deal with the extra work. Such was the public interest, Forest & Bird gave daily updates to the media on the number of people who had signed the petition.

“We have received a great volume of correspondence applauding our efforts, including from overseas: USA, Britain, Australia, Canada, and even Teheran,” said a Forest & Bird editorial.

People from all over the country and all walks of life (and political hue) became involved in the Save Manapōuri campaign. Some would go on to become giants in Forest & Bird’s conservation history, including Sir Alan Mark, Judith Piesse, Fraser Sutherland, and Fraser Ross, among many others.

Commercial lawyer Harry Anderson, who would later turn down an offer to become a Supreme Court judge, went around Wellington asking people to sign Forest & Bird’s Save Manapōuri petition.

His grandson Harry Broad says: “The campaign cut across all sectors of society and all classes, including National supporters like my grandfather. It cut across a lot of borders, and a lot of people you wouldn’t think would care actually cared very deeply about Manapōuri and what was happening.”

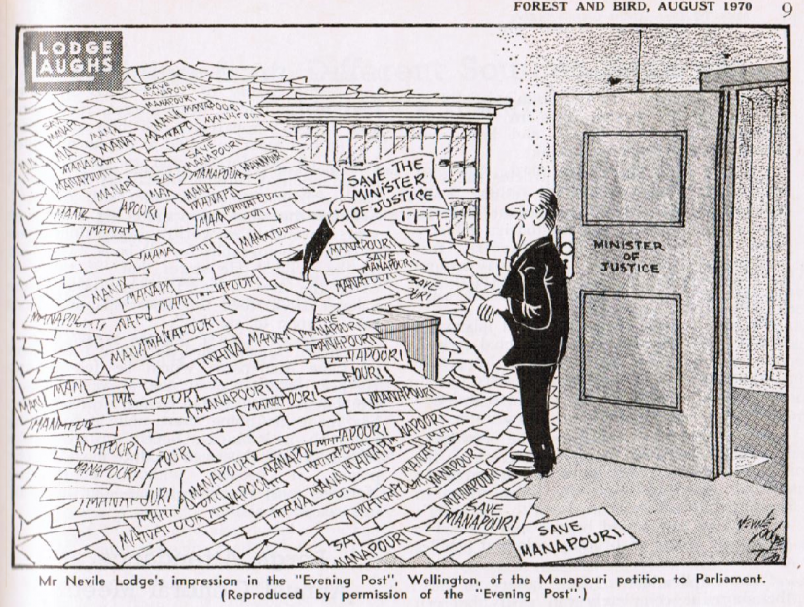

Nevile Lodge’s 1970 cartoon about Forest & Bird’s record-breaking Save Manapōuri petition was reproduced in Forest & Bird’s journal.

After receiving the petition, the government came out fighting. The Minister of Works and Electricity, Percy Allen, tried to undermine it by claiming up to two-thirds of the total signatories were children too young to know what they were signing. ‘Prove it!’ was the response of Roy Nelson, Sir Jack Harris, and various newspaper editorial writers,” says Neville Peat, in his book Manapōuri Saved! Allen later admitted he had not perused the petition and the figure was a guesstimate.

Our archives show that the Forest & Bird petition prompted National Prime Minister Keith Holyoake to appoint a Manapōuri select committee, which met in November 1970.

But first there was the matter of the Commission of Inquiry to deal with. Forest & Bird worked alongside the Save Manapōuri Committee, sharing half the cost of retaining legal counsel Frank O’Flynn to present the conservationists’ case to the inquiry, which sat for 38 days from June 1970 and received more than 2000 pages of evidence.

Meanwhile, as Neville Peat says, “the war of words spilled out onto the streets”, with a noisy rally outside the select committee in Wellington in 1970 and, later, protests in Invercargill during the opening of the Aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point, in 1971.

Labour seized power in 1972, and the new government, keeping a promise made during the general election, agreed not to build the high dam planned for Manapōuri or change lake levels.

The campaign was won. And, in an unprecedented move, the government went on to establish the ground-breaking community led watchdog Guardians of Lake Manapōuri in 1973.

Forest & Bird’s Force of Nature history project has uncovered new images, archives, and film footage about Manapōuri.

A version of this story first appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.