Youth Creature Feature [July 2025]

You can't fault them for sticking to what they do best.

By Jasmine Starr

Stick insects. Stick bugs. Rō, Whē. Or, in my family, a guttural “sticky!!!” We all know them, we all love them, and we all scream excitedly when we see them. There are 23 species of stick insect in Aotearoa alone…but, by far, my favourite is the smooth stick bug.

The smooth stick bug—also known as the common stick bug—is a flightless, mostly-female- sometimes-asexual legend that lives on only three islands across the globe. They’re masters of hiding in plain sight, but likely the species you’ve seen most. You can tell this species from the other 23 by a long, vertical line down the centre of their body. However, while they are striped, they’re very hard to spot.

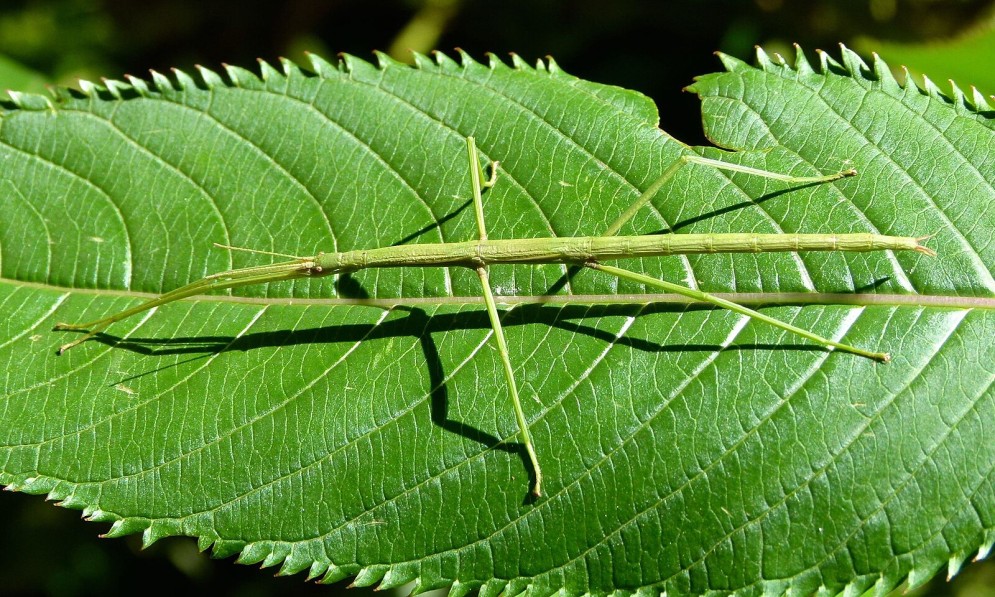

I am blending in. I am exactly this colour. I was never here. You can’t see me. Credit: Christopher Stephens, iNaturalist via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

As you may well know, stick insects look a whole lot like sticks. Everything from their imperfect woody texturing to their spindly limbs just screams “I’m part of a tree!!”, even though stick insects are incapable of sound (and don’t have ears, either). They move slowly or not at all, and will wave in the wind just like a real stick. Even their leg joints echo branch offshoots and nodes.

This species has incredible variation in colour—they can be any shade from reddish to grey to new-shoot green, all the better to blend in with multiple environments. While browner stick bugs prefer branches, some green stickys will position themselves across a leaf, their body as a stem, their legs as veins. Camouflage isn’t even limited to the adult stage—smooth stick bug eggs look just like plant seeds!

What betrays this brilliant disguise is sheer perfection. Real sticks don’t have six evenly spaced legs, or consistent segments on their abdomen. They also don’t have beady little eyes, wiggly antennae, or a limitless capacity for bringing humans joy.

But their camouflage isn’t just a conduit for delight. All their predators hunt via sight, so it also serves as a safety mechanism—though their disguise works differently on different creatures. The way humans see (or fail to see) these insects is through a process called background matching. It doesn’t ‘stick’ out of its surroundings, so our eyes scan past it. Their natural predators, birds, have a different mental process. They do see the bug, along with every other branch in the area. Instead of missing it entirely, birds very consciously mistake it for a run-of-the-mill inedible twig.

I am not a stick bug. I am a stick. I am straw. I am dirt. I am the wind. You can’t see me. Credit: Valemereu, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0.

Males have to move around to find a mate, which means predators can clock them far easier. To compensate, they measure 6.7 to 7.4 centimetres in length—significantly smaller than females. Being tiny helps them blend in, hide better, and avoid their predators. But females stay put…so they have no such qualms. If males are a twig, females are offshoot branches—thick, bulky, and long, measuring from 8.1 to 10.6 cm. That’s a box and whisker graph with no overlap.

You can find these stick bugs munching on mānuka, kānuka, or coprosma, or chilling on walls in your very own backyard. They’re scattered across the North Island, and found on coastal edges of the South—such as Kāikoura, Ōtautahi Christchurch, Whakatū Nelson, and Ōtepoti Dunedin. The smooth stick insect hasn’t been found on any other islands—except for Great Britain!

While we don’t share the smooth stick insect with anyone else in the world, it is found across the Scilly Isles. That’s right—this time, Aotearoa’s creatures have invaded Britain! We have introduced three stick bug species of our own, via plants shipped to English nurseries. They’ve managed to flourish, snacking on roses, various brambles, and wild privet. Fortunately, all three are naturalised, and pose no threat to the local wildlife. Though Britain has no native stick bugs, now you can find them all over the south!

Well. You can find females all over the south. That’s right: literally every smooth stick bug in England is female. How is this possible? Parthenogenesis!

Despite coming from a sexual population in Taranaki, all of England’s smooth stick bugs reproduce asexually. Using a process called parthenogenesis (‘virgin creation’), females give birth to what are essentially clones of themselves, without needing a male to fertilise. And, being clones, their child ends up female, too. Their ability to reproduce alone means the entire UK population could have started from just one female egg.

I am a leaf. A veiny leaf! Shadow? What shadow? Your mind plays tricks on you. You can’t see me. Credit: Steve Kerr, iNaturalist via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Smooth stick insects can reproduce sexually or asexually, depending on what is essentially societal norms. If there are some stick bugs in an area that mate, every stick bug in that area will mate. Likewise for asexual reproduction—though they can switch back and forth, depending on male population. Across the North Island, sexual reproduction is the norm, and males are still widespread. On the South Island, males are increasingly rare. There has never been a male smooth stick bug sighted in the UK.

But for the ones that mate…oh boy, do they mate. Females will signal to males by hanging off a branch and releasing oodles of volatile chemicals called pheromones. The males smell this, and for some reason (sex) decide to seek it out. Once the male traces the scent and the stick bugs start mating, they will stay attached to each other for days to weeks. The male rides around on the female’s back, repeatedly mating all the while. I understand why they’d want to reproduce asexually, and skip all that hassle!

Next time you’re in a garden, look carefully at the branches and twigs. Are there any beady little eyes? Perfectly spaced segments? Wiggly antennae? Do you feel a spontaneous burst of joy welling up inside you? If not, it’s likely just a stick. …Or is it?

Youth Creature Feature is your monthly dose of Aotearoa New Zealand's wacky, whimsical, and wonderful native and endemic species.

Want to get in touch?

Maybe you'd like us to write for you. Or you'd like to write for us?

Contact: Forest & Bird Youth Editors