From Singapore to Copenhagen, forward-thinking cities are weaving green spaces into their urban fabric and welcoming wildlife home. By Caroline Wood

Little forests, Tokyo, Japan

Forest & Bird Magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Summer 2025 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

The majestic Meiji Jingu forest, planted a century ago, continues to mature according to Dr Honda Seiroku’s visionary 150-year plan for a self-sustaining “eternal forest.” Guided by local experts Dr Li Qing and Dr Imaizumi, Wild Cities author Chris Fitch explores the therapeutic benefits of shinrin-yoku forest bathing and discovers how the Miyawaki method can create thriving “mini forests” in compact urban spaces. His journey also takes in Shintō shrines – ecological havens where Japan’s indigenous spirituality and nature conservation have flourished together for centuries. Tokyo shows how urban dwellers in big cities can connect with trees in multiple ways. As well as helping keep the city cool and providing safe spaces for nature, street greenery boosts residents’ physical and mental health.

Meiji Forest, Tokyo. Image Chris Fitch

Garden city, Singapore

Singapore’s transformation from biodiversity loss to “City in Nature” proves urban conservation works. The visionary Garden City initiative reversed habitat destruction, led to the planting of thousands of trees, and created urban nature reserves. Buildings now host thriving ecosystems – butterflies, squirrels, and birds flourish on vertical gardens climbing 200m skyward. Government incentives greened existing structures, making rooftop forests normal across the skyline. Hospitals designed with nature accelerate healing and attract endangered pangolins. From forest devastation to hosting 100+ bird species, Singapore demonstrates that cities can regenerate wild spaces. Every building is potential habitat; every city can choose nature.

Kampung Admiralty, Singapore. Image Chris Fitch

Room for rivers, Munich, Germany

Restoring the River Isar made it swimmable for residents and allowed Eurasian beavers to return to Munich, Germany’s third-largest city. Engineered into a straight channel in the 19th century, the river was prone to flooding, ecologically degraded, and inaccessible to locals. The Isar Plan, launched in 1995, was a nature-based solution offering flood protection with co-benefits: habitat restoration, landscape enhancement, and recreational use. The riverbed was widened and weirs removed, restoring native fish and birdlife. Public access points were added along the riverbanks, now safe for swimming. Giving rivers room to roam can reduce flood risk while supporting biodiversity. Restoring urban waterways to a natural state benefits wildlife and communities.

The restored River Isar, Munich, Germany. Image Chris Fitch

Edible streets, Copenhagen, Denmark

Copenhagen has revived ancient Danish foraging traditions through its “edible streets” movement. Denmark’s medieval Code of Jutland established foraging rights – but people could only take what fitted in their hats. Chris meets professional foragers, chefs, and educators who show him how wild plants thrive on pavements, roadsides, and forgotten urban corners. Pineapple weed, sweet cicely, wild rocket, nettles, apples, and mushrooms are some of the foods gathered and used in local homes and restaurants. Residents can use a free app to find food growing wild in the city. Chris says this democratises foraging knowledge by mapping locations and identifying edible plants, so everyone can access fresh food. Today, a sustainable foraging movement is resurging in Europe and around the world, including Aotearoa. FallingFruit.org helps residents find free food in their neighbourhood through a collaborative global map with more than 500,000 free urban food sources around the world.

Copenhagen, a city where restaurants use wild foraged ingredients. Image Chris Fitch

Wildlife capital, Nairobi, Kenya

Nairobi National Park – the world’s only wildlife capital – brings Africa’s iconic big game animals to the city’s doorstep. Lions, giraffes, zebras, buffalo, rhinos, and even baboons roam just kilometres from downtown skyscrapers. While the 117km² national park faces pressure from urban expansion, local Kenyans fiercely protect it. Unlike remote safari parks serving wealthy tourists, Nairobi National Park welcomes hundreds of thousands of residents, including children, at affordable prices. This accessibility creates passionate conservation advocates among urban Kenyans. Young activists like Felix Mutwiri and Elizabeth Wathuti are championing the park’s protection. As city residents connect with wildlife in their backyard, they become lifelong defenders of Kenya’s natural heritage, Chris.

Zebras in Nairobi National Park. Image Chris Fitch

Marine reserves, Sydney, Australia

Sydney Harbour demonstrates nature’s remarkable recovery when depleted marine ecosystems are given a helping hand. Once hunted to near-extinction, fur seal populations have rebounded to pre-colonial levels through strict protection measures. The harbour now shelters nearly 600 fish species. Living seawalls transform artificial structures into thriving habitats, and support biodiversity. Cabbage Tree Bay’s no-take marine reserve is a huge conservation success – protected blue groper control sea urchin populations and preserve kelp forests while inspiring other communities to demand similar sanctuaries. From Aboriginal sustainable fishing practices to modern marine parks, Sydney proves ocean protection works. When people witness nature thriving in small marine sanctuaries, they demand more protection everywhere.

Cabbage Tree Bay, Manly, Sydney. Image John Turnbull/Flickr

Green corridors, Medellin, Colombia

Colombia’s second-largest city, Medellín, has created more than 30 green corridors to reconnect fragmented urban nature. These vegetated pathways – running alongside roads, streams, and metro lines – link isolated pockets of greenery, allowing wildlife movement and reducing vulnerability to environmental shocks. The initiative added 2.5m plants and nearly a million trees citywide, supporting future climate resilience. Landscape architect Marcela Noreña Restrepo tells Chris the key is “integralidad”, understanding these corridors as an interconnected system that allows nature to permeate throughout the city, rather than being isolated decorative elements.

Avenida Oriental, Medellín, Colombia. Image Chris Fitch

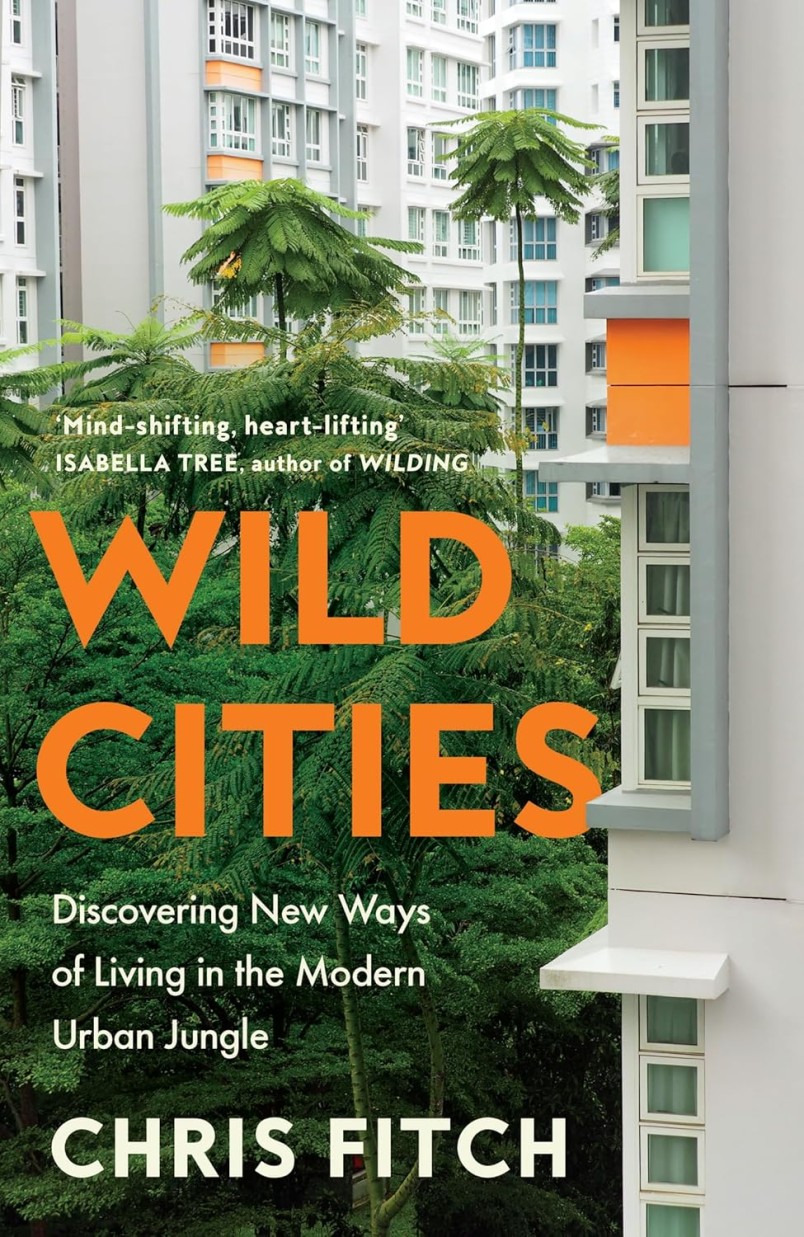

For more inspiring stories like these, see Wild Cities: Discovering New Ways of Living in the Modern Urban Jungle by Chris Fitch. We have two copies to give away – see below.

Win a book

We have two copies of Wild Cities by Chris Fitch (William Collins, RRP $37.99) to give away. By 2050, two-thirds of us will live in cities. In this thought-provoking guide, the author embarks on a global journey to meet people passionate about rewilding their urban spaces. Fitch argues that daily contact with nature benefits residents, biodiversity, and the climate. After visiting 12 cities, he concludes that nature in urban spaces isn’t a luxury – it’s essential for our health and happiness.

To enter, email your entry to draw@forestandbird.org.nz, put WILD CITIES in the subject line, and include your name and address in the email. Or write your name and address on the back of an envelope and post to WILD CITIES draw, Forest & Bird, PO Box 631, Wellington 6140. Entries close 1 February 2026.