Youth Creature Feature [September 2025]

Bird of the Year special. Here's introducing you to an adorable manu who is sure to steal your hearts and make you join the #WryForce

By Jasmine Starr

Every year, I vote in the Bird of the Year competition. And every year, my votes are determined through a complex system of 20 weighted categories. From vulnerability to legginess to the accuracy of its name, these fine-tuned equations turn my avian joy into solid numbers. And this year, one humble odd-beaked river bird took my spreadsheet by storm.

As regular Creature Feature readers may know, I cannot resist a glorious nose. Whether it’s spoonbills or matuku or the subantarctic snipe, I am spoiled by schnozzes every year. But while it may not be flashy, the aptly named Wrybill has the wryest nose by far.

Sitting beneath a thick feathered brow, the Wrybill’s beak is long, dark, and curved sharply to the right. Appropriately dubbed ngutu pare (‘diverted beak’) in te reo Māori, the wrybill certainly lives up to its names. In some photos, its bill looks almost like a hawk’s beak turned sideways, the sharp tearing tip pointing straight towards their wing. Perfectly shaped to forage under stones, the wrybill’s bizarre, curved beak is the only one of its kind. Take that, six species of spoonbill.

The marvellous wrybill, its beak as wry as ever. Credit: Nick Athenas via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

This smartly monochrome shorebird lives in a misty world of grey. They forage under greywacke shingle and river stones, picking across misty braided riverbeds, beneath enormous, rocky South Island peaks. Braided riverbeds are series of river channels, interwoven with each other, creating small sandbar-esque islands. Wrybills frequently move in wide circles; because of their laterally curved beak, they forage only on their right-hand side!

Their chicks are heartmeltingly cute balls of fluff with eyes, planted atop disproportionately long legs. The slapdash way they move is absolutely adorable—sprinting and slipping and wandering around, flat feet slapping across the stones. They look like beings built of enthusiasm, terror and general confusion. It’s the greatest, clumsiest, most intensely charming walk I’ve ever seen.

The adults aren’t much better. With the unmistakable feeling of ‘pulling off a dance move after you trip’, these regal, mysterious birds are bumbling, twitchy, and sprint like they’re playing Grandma’s Footsteps. With knobbly knees and an irresistible charm, the wrybill is a clear choice for BOTY 2025.

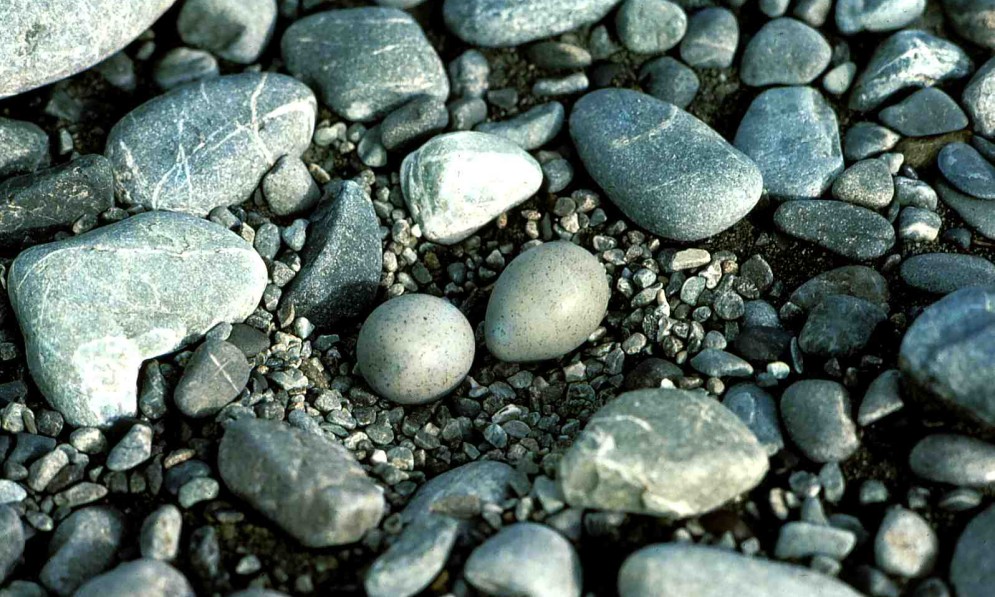

Wrybill eggs in their incredibly minimalist nest. Credit: John Hill via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Wrybills nest on the ground, by scraping the slightest indent into the greywacke gravel and plopping their eggs inside. If this sounds vulnerable, don’t worry—the wrybills have a cunning technique to lure native predators away from their nests. When alerted to danger, these clever creatures will fake an injury—angle their wing like it’s broken and drag it across the ground, pretending to be easy prey. When the predator gives chase, they’ll flap away at the last minute!

If you assumed these birds were ground-dwelling by default, well, me too. This is far from the truth. Wrybills migrate up and across Aotearoa every summer, travelling hundreds of kilometres from braided rivers around the Southern Alps to as far as Karikari. They settle in estuaries and harbors across the North Island, particularly in Manukau and the Firth of Thames. During migration season, they can be seen in large clusters across the South Island’s waterways, particularly at Canterbury’s Lake Ellesmere.

But their flight patterns aren’t just surprising. According to some, they border on the supernatural.

Yes, those are BIRDS. Credit: Adrian Riegen via Pūkorokoro Miranda Shorebird Centre.

Their collective noun dubbed ‘a flung scarf’, the wrybill’s flight patterns are spectacular. Hundreds of wrybills take to the air in an incredible coordinated ballet, winging as one in a gossamer chain, an amorphous flapping mass of birds. As they weave around each other, their snow-white stomachs flash in turn, switching from grey to white to grey again in a spellbinding canon. Their flights are so intensely synchronised that a 19th century ornithologist, Edmund Selous, was convinced they used telepathy.

Anyone in conservation circles is used to the constant threats our avian taonga face. Introduced mammals, like ferrets, stoats and hedgehogs, eating eggs out of ground nests and sniffing out camouflaged creatures by smell. Humans, polluting rivers, crushing habitats, flooding nests with dams or wash from recreational boats. Invasive species, or quickly spreading plants like mangroves, encroaching on and fatally altering their ecosystem. Irrigation. Eutrophication. Off-leash dogs. You know the drill.

A frustrated wrybill wondering why it hasn’t yet won BOTY. Credit: ‘Amaya M’ via iNaturalist, CC BY-NC 4.0

The wrybill faces all of these threats, and more. With an estimated 4,500 birds remaining worldwide, the wrybill is rightly listed as “in serious trouble”—and it’s only declining. A Bird of the Year win would mean visibility. It would mean help, donations, and awareness of the braided river ecosystem. The awareness raised by BOTY will help this goofy species live on, not just in our hearts.

BOTY’s past winners are flashy, colourful, well-known creatures like the kea, kākāriki, or kererū. But don’t acquiesce to the creatures we all already know and love. This year, let’s put the spotlight on this obscure wry-beaked wonder, flapping and flopping and slipping its way to victory. Vote Wrybill for Bird of the Year by September 28th, to help the one and only sideways-beaked bird survive into the future.

Youth Creature Feature is your monthly dose of Aotearoa New Zealand's wacky, whimsical, and wonderful native and endemic species.

Want to get in touch?

Maybe you'd like us to write for you. Or you'd like to write for us?

Contact: Forest & Bird Youth Editors